🔮 Sunday edition #535: Generalist robots; AGI & debt; energy realism; AI talent wars, fertility math, attitudes++

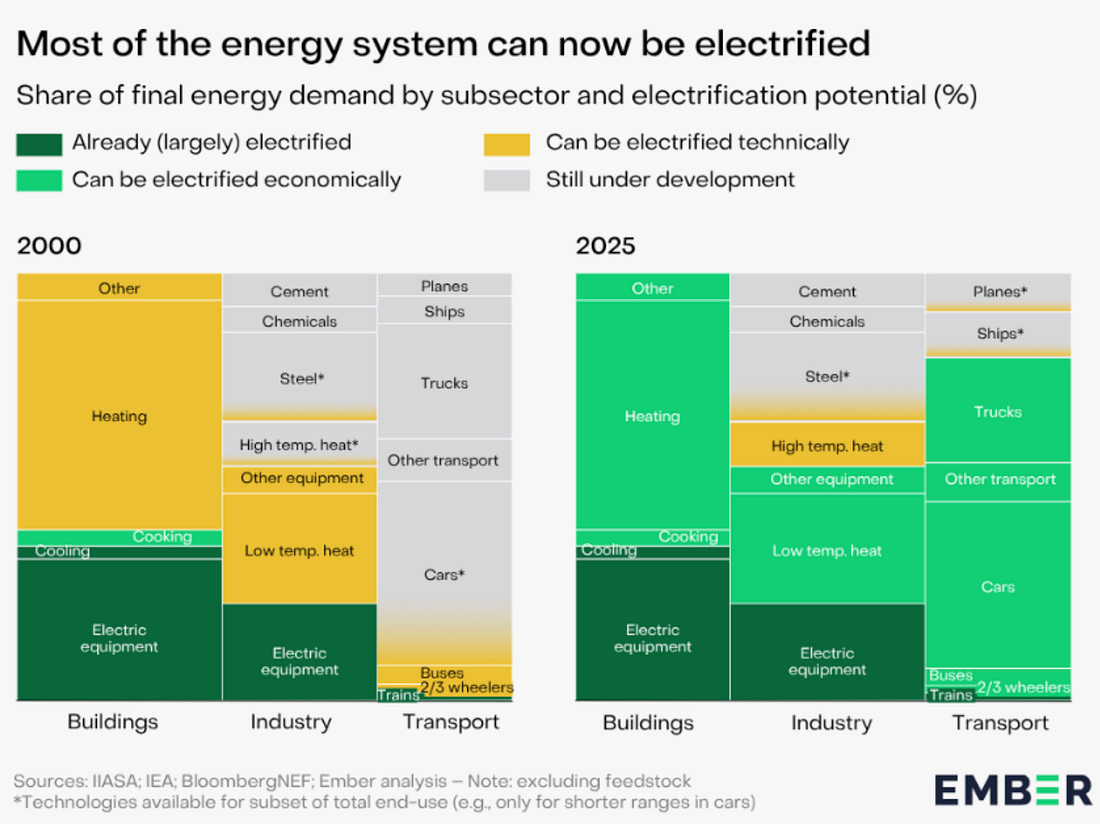

🔮 Sunday edition #535: Generalist robots; AGI & debt; energy realism; AI talent wars, fertility math, attitudes++A weekly dive into the trends, tech, and ideas remaking our world.Hi all, Welcome to our Sunday edition, where we explore the latest developments, ideas, and questions shaping the exponential economy. Thanks for reading! Azeem We don’t need miraclesThe debate over clean energy’s future is increasingly polarized over how far current solutions can take us. One camp argues that the transition is already stalling under the weight of political and economic constraints. The other believes in scaling newer, more ambitious technologies despite their high cost or unproven readiness. There is a pragmatic middle, however. My friend Michael Liebreich, as always, offers a grounded take. His model shows that as long as clean energy continues to outgrow overall energy demand by a few percentage points annually, fossil fuels will inevitably be squeezed out of the system. The transition doesn’t depend on breakthroughs or miracles. It depends on compounding growth, year after year, where clean energy keeps expanding faster than demand. In 2000, much of the global energy system was either unelectrifiable or stuck in the “technical but uneconomic” zone. By 2025, a substantial share of final energy demand across buildings, industry and transport is economically electrifiable.

If the energy transition depends on compounding progress, China’s nuclear strategy is a lesson in what that compounding can deliver. The country has defied the global trend of rising nuclear costs. It now delivers reactors at about $2–$3 per watt – far less than recent US projects like Vogtle 3 and 4, which have hit up to $15 per watt. China scaled through standardized designs, local supply chains and a stable industrial policy. As a result, it could overtake the US in nuclear capacity by the early 2030s. Token production = debt reduction?Coatue Management argues that AGI could stabilize the US debt-to-GDP ratio¹ around 100% by 2034. With artificial superintelligence, it might even fall to 80%. This is well below current projections of ~120–140%. It’s an enticing vision. The full keynote by Philippe Laffont, the firm’s co-founder, is worth watching. But the forecast seems to assume a causal chain: more intelligence leads to more productivity, which lifts GDP and eases the debt burden². Our economy, though, is anything but linear. If AGI’s productivity gains accrue primarily to capital, workers could see their incomes stagnate or decline even amid rapid economic growth. Research from the Philadelphia Fed shows that labor’s share of income has fallen since 2000 (see here and here). If that trend continues and corporate taxes remain porous, governments may struggle to raise sufficient revenue to fund public services or counter rising inequality. In that world, the cost of running an AI puts a cap on wages. The benefits of growth go to those who own the machines, not the workers they replace. Still, Coatue’s provocation is a useful springboard for ideation. If AGI reconfigures productivity itself, how should we rethink the metrics and institutions around it? What replaces GDP when so much economic activity is generated by open-weight models or intelligence priced at zero? Could governments one day issue cognition-backed bonds – claims not on future labor, but on future machine-generated services? And if human work no longer anchors the tax base, do we begin taxing compute or auctioning AI time? I discussed some of these ideas for the next twenty years with economist Tyler Cowen, if you’d like to dig deeper. A general-purpose robotWe may be further along the robotics maturity curve than is widely appreciated, argue Dylan Patel and his team at SemiAnalysis. They’ve mapped out a five-stage framework tracking how robots are progressing from rigid, pre-programmed machines (Level 0) to autonomous systems capable of fine, human-like manipulation (Level 4). We’re now in Levels 2 and 3: robots are navigating messy environments and performing some low-skill tasks like folding laundry, cooking and warehouse restocking. This is as much about technology as it is about economics and labor markets. In parcel logistics, SemiAnalysis estimates that ten robots can match the output of 23 human sorters. They go on to show that per-pick costs for robots fall below human rates in just over a year. As robots gain dexterity and tactile intelligence, we’ll step into Level 4 where the scope of automatable work could expand dramatically. Level 4 would cross into tasks we thought robots couldn’t touch, like skilled trades, fine-grain manufacturing, or even caregiving. Elsewhere:In tech + AI:

In society + culture:

Inside companies:

Thanks for reading! Today’s edition is open to everyone – if you found it valuable, share it widely. 1 Debt-to-GDP measures a country’s total public debt relative to its economic output. Lower ratios generally indicate more fiscal room and stability. 2 Note: We don’t have access to Coatue’s underlying model, a key input in any analysis. |

Similar newsletters

There are other similar shared emails that you might be interested in: