What engineers get wrong about communication

What engineers get wrong about communicationThe do's and don'ts of effective communication for product engineersEngineers spend most of their time doing two things: coding and communicating. The first has endless amounts written about it; the second much less so. To address this injustice, we're sharing:

1. Forgetting about your usersIt’s easy to get caught up in the technical details of a project, such as overcoming constraints, optimizing performance, and following best practices. But companies don’t succeed based on their ability to solve technical problems. They win when they solve their user’s most painful and valuable problems. This should be reflected in your communication. At PostHog, our communication connects to users in one of two ways:

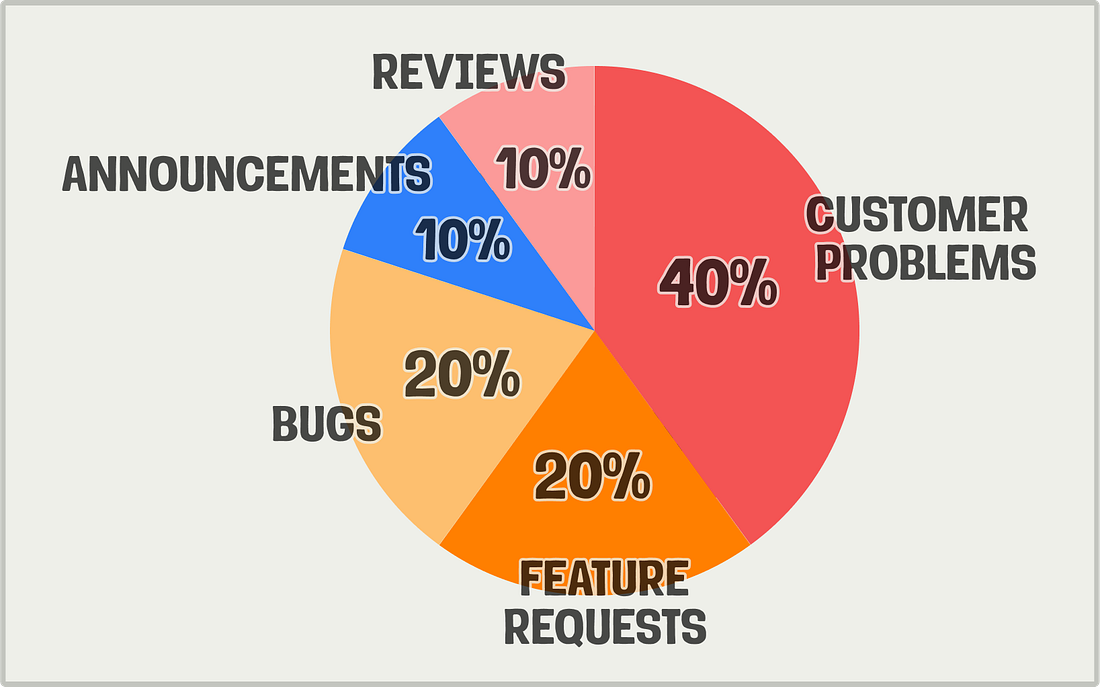

To give you a sense of what this actually looks like, a snapshot of the last 10 Slack messages in our #team-product-analytics channel includes:

In other words, 80% of the communication was about problems customers had, or requests for features of changes to improve the experience. This user focus does have tradeoffs: we spend less time discussing technical details, figuring out the best way to do things, and collecting input from stakeholders. Instead, we rely on:

Sometimes this means we aren't shipping a perfectly polished feature right away, but the benefit is we can get to something that users actually care about faster.

2. Hoarding information (aka Squirrel Mode)People tend to hoard information. They are scared sharing it will make them look silly, or lose the power they think it provides. But this attitude kills companies. Knowing things isn’t a super power, sharing what you know is. You’re not a squirrel. Hoarding information causes three problems:

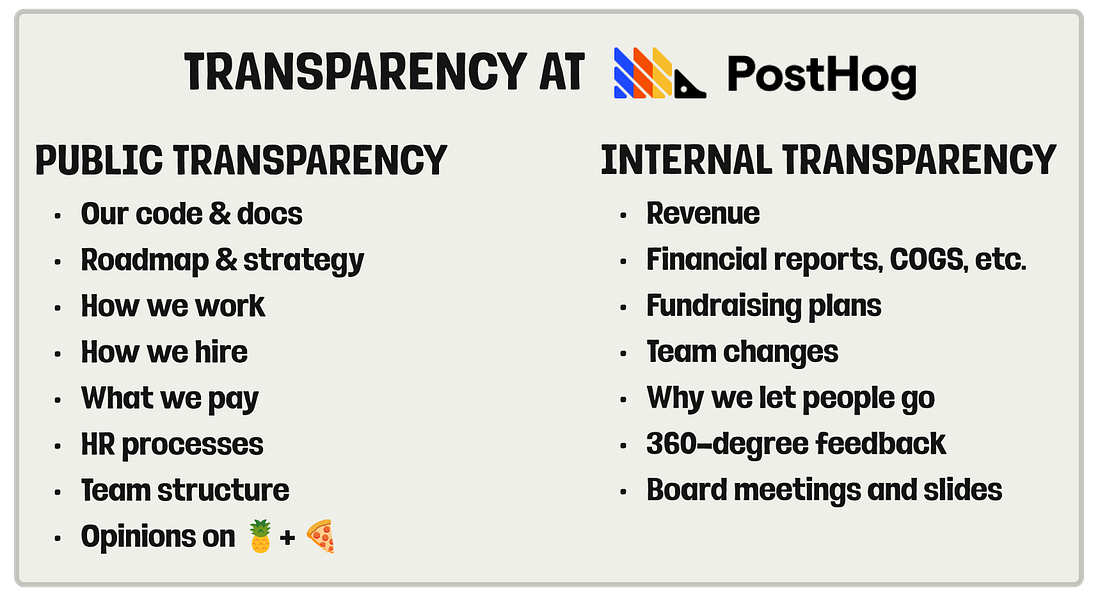

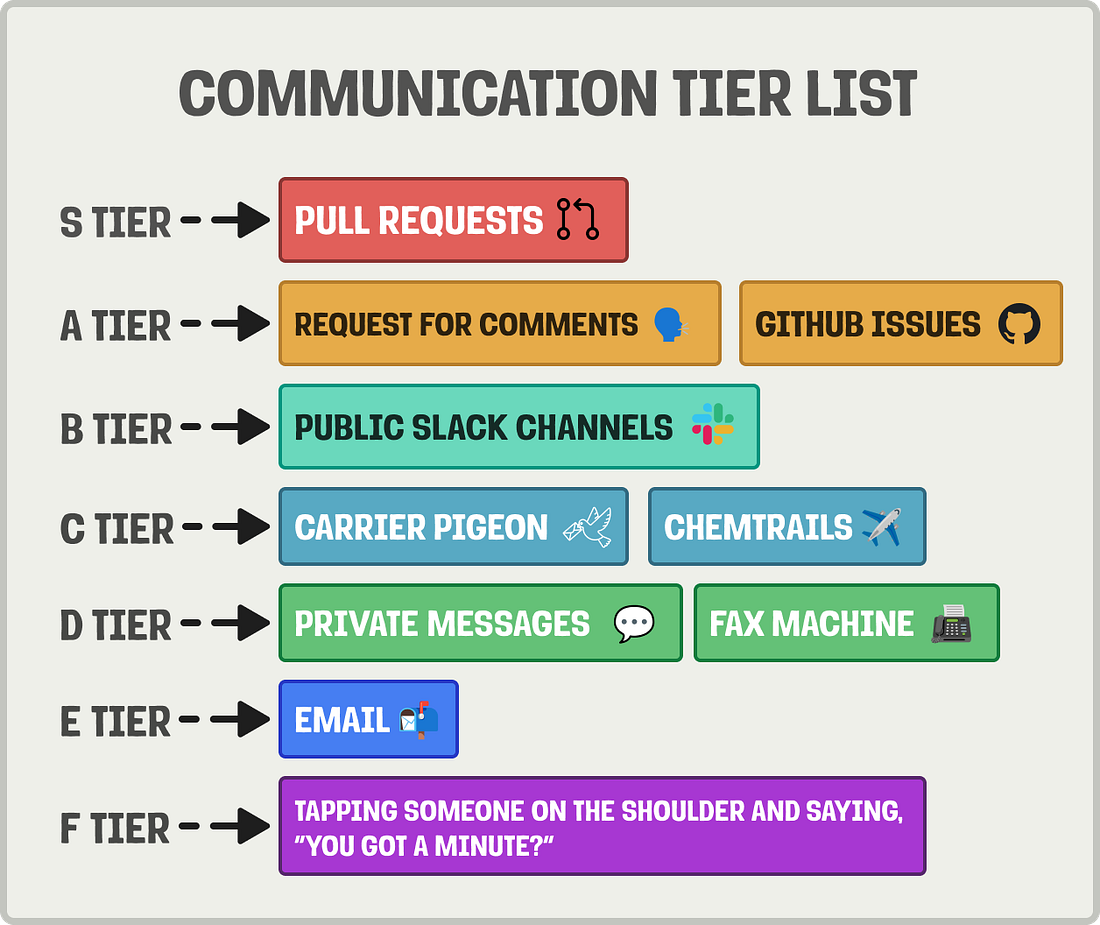

The solution is to make communication legible: write it down and work in public. This means avoiding closed door meetings, private Slack conversations, and email threads, whenever possible. Instead, move communication to public channels, have an accessible wiki or handbook, and default to giving everyone access to everything. But this only works if it comes from the top. At PostHog, the exec team shares details that are often private at other companies, like company finances, slides from board meetings, or the reasons for letting people go. In doing this, they encourage everyone else to do the same. Hiding engineering knowledge looks trivial in comparison. We also take "working in public" a step further by sharing as much as possible publicly, outside our company. This includes our code, roadmap, and even strategy. Sharing so much context publicly compounds its impact. It builds trust with customers, and means potential candidates and new starters arrive having already consumed the context they need to have an immediate impact. We realize external openness doesn't work for everyone, but that doesn't mean you should return to hoarding information. Companies like Palantir, Pixar, and Meta are all secretive externally, but have internal openness. This has helped them build the massively successful companies they are today.

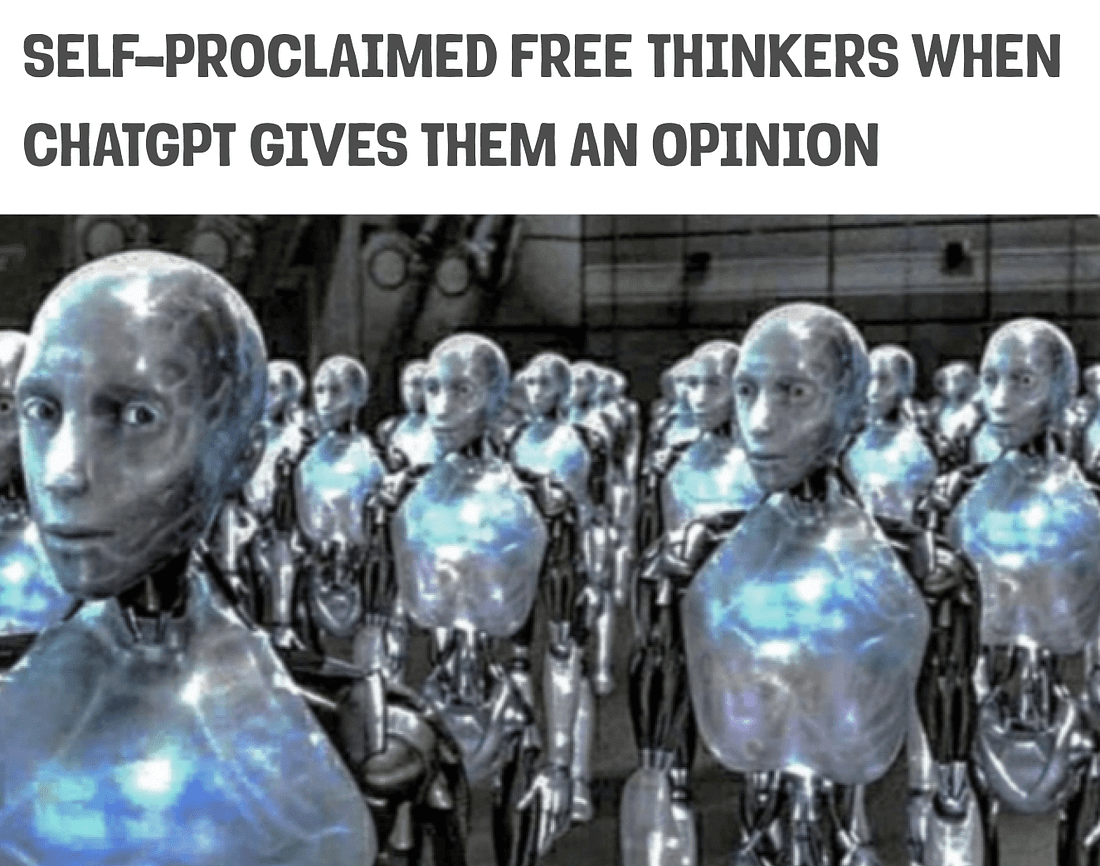

3. Lacking an opinionOpinions are direction. They are what your product and company become. People who don’t communicate in an opinionated way are easily ignored, and often resent their lack of influence. To avoid this outcome, it’s critical to do the work to actually form an opinion. Relying on whatever comes to mind (or whatever ChatGPT tells you) will leave you directionless and undifferentiated. When sharing an opinion, ask yourself:

One way I do this is to anticipate what my smartest coworkers (or competitors) might say in opposition to an idea or opinion, and then ensure I back up my points with enough to stand them up. A process sometimes referred to as steelmanning. Our request for comments (RFC) process exemplifies this approach. When someone creates an RFC, they don't just say there is a problem, they propose a specific solution, take a stand on why it's right, mention alternatives, and invite feedback. Once you’ve done the work to form an opinion, be confident and direct in sharing it. Don't hedge by saying "this might be a good idea" or "maybe we could do this." Vague, non-committal communication might feel safer, but it rarely leads to action. Being opinionated (and sharing those opinions clearly) enable us to move faster and more autonomously. Teams don't wait to be assigned tasks or told what to do. They identify problems and go solve them.

4. Not including enough contextLow context messages like “this isn't working” or “what do you think of this?” suck. They burden the receiver with figuring out the context, so they can work towards a solution. They sap energy out of others. This problem is common in remote companies, especially ones wedded to old habits formed from working in an office. In remote settings, you can’t see the blank stares and distracted looks of people you’re losing. You need to account for this by including all the context a reader needs to succeed. This usually means sharing:

Sharing the context gives the receiver more of the information they need to evaluate the problem as well as a jumping off point for finding a solution. Likewise, when asking a question, provide both the question you have AND the reason you’re asking. This can save a lot of back and forth, and often leads to a better solution than the one you assumed existed.

5. Being completely unstructuredPeople want to communicate. They want to distribute information with each other. Information wants to be free. It can be tempting to let people do whatever they feel is best, but this can quickly devolve into one of two problems:

Fixing this requires giving people a time and place to communicate. You can think of these as "rituals," repeated, formatted moments to encourage communication. They help teams stay aligned and make sure everyone has what they need to succeed. Our rituals include:

Rituals aren't unique to PostHog. Zapier requires Friday Updates from everyone on their internal blog. Basecamp has daily and weekly check-ins as well as kickoffs and heartbeats. Linear works in two-week cycles, writes project specs, and keeps an updated changelog. All rituals, including ours, are downstream from the culture you want to create. For us, that means they are as async as possible and involve as few meetings as possible. This ensures that we have enough time to work on what's important.

6. Not making communication actionableOrganizations tend to add process and structure as they grow, which slows them down. Communication is one of the areas that this can pop up, so you need to be constantly fighting against this tendency. We do this by:

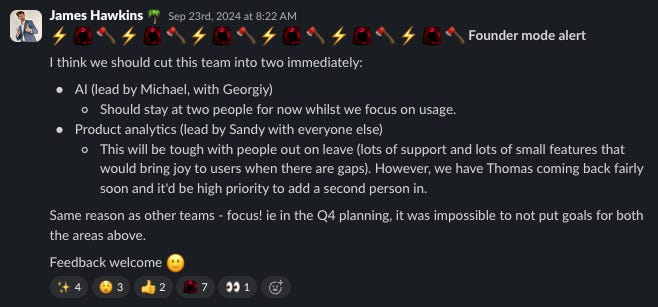

A piece of communication that best represents this action-orientation is our team splits. Usually, a new team forming would take weeks (or months) of meetings and planning. At PostHog, it takes the form of a single message with a lot of 🪓 and 🚨 emojis. This is direct, gives only the important context, and provides clear owners and next steps. This helps everyone get back to what’s important: shipping. What happens when you avoid these mistakes?

Don't believe this is real? This is largely how communication works at PostHog and based on a recent internal survey, it seems to be working.

Although communication can always be improved, avoiding these mistakes goes a long way in doing it as well as possible. Words by Ian Vanagas, self-proclaimed free thinker. |

Similar newsletters

There are other similar shared emails that you might be interested in: