How startups lose their edge

How startups lose their edgeA first hand account of how "playing not to lose" can accidentally kill your startup

In American football, there’s a strategy called “prevent defense” that teams use when they’re leading late in the game. The logic is sound: give up small gains but prevent big plays, run out the clock, and protect your lead. It’s conservative, it’s textbook, but it often backfires. The problem isn’t the strategy itself. It’s that you stop doing the things that got you ahead in the first place. You’re no longer playing to win, you’re playing not to lose, and in sports, in startups, in anything competitive, that shift in mindset is how you hand the game to someone hungrier than you. I know because I saw this happen. I was one of the first 30 employees at a now public tech company you’ve probably heard of. When I joined, it had something special: tight culture, developer-first mindset, and a product-led motion that got us to hundreds of millions of annual revenue before thinking about sales. Importantly, the founding team kept an iron grip on who got hired, the bar was high, and everyone who made it through understood what it meant to be part of the culture. But you can’t scale to IPO with founders interviewing everyone. You have to let go. Culture becomes a game of telephone. The message stays mostly the same, but with each repetition, it drifts just slightly. Over years, those slight drifts compound and alter the trajectory of the company into an outcome 5-10x lower than it could have been. I don’t want this to happen to your startup, so here’s how to avoid it. When priorities shiftThe inflection point came when an IPO became a tangible reality. When there’s real life-changing money on the table for everyone involved, it becomes incredibly easy to make concessions. Suddenly “just this once” starts to sound reasonable.

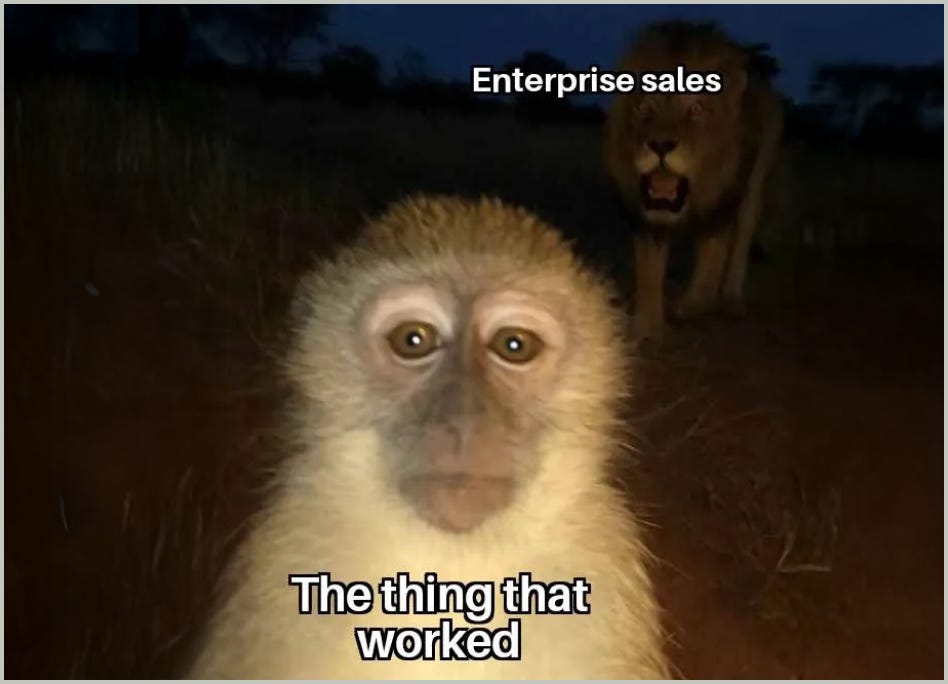

Culture wasn’t the only thing that mattered anymore. Instead, we needed people who had “done this before,” experienced leaders who knew how to navigate public company requirements, quarterly earnings calls, and all the machinery that comes with being a real grown-up company. The biggest example of this was hiring an entire sales team as a siloed function, separate from the product-led sales motion that got us to hundreds of millions in ARR (annual recurring revenue). We needed to grow faster, enterprise sales seemed like the obvious answer, and everyone does it eventually, right? Prior to doing this, we had a technical team that was consultative-first, helped businesses leverage the products we built, and taught best practices. We were measured on net revenue retention and customer expansion. That shifted. The technical folks took a back seat to the veteran enterprise sales people, who had no domain expertise or technical knowledge. We became a supporting function in service of sales. It sucked. I watched our existing team who got us so far relegated to supporting the traditional sales team. I’m not against building out a sales team, the problem was how we did it. It was a completely separate motion divorced from what had actually worked, optimized for what public companies are supposed to do instead of what had made us successful. It was a cultural concession that completely changed the trajectory of the company. The culture dilution problemAlthough we were making a lot of cultural concessions, the company didn’t become a bad place to work. It kept doing good things up and through the IPO and beyond. The culture didn’t become toxic or negative. It just became boring. We stopped doing the wild, wacky, weird things that made us special in the first place. Culture isn’t some abstract value statement printed on office walls (that’s gross and tacky). It’s every person, decision, priority, and judgment call about what matters. Dilution happens gradually and it’s almost invisible while it’s occurring.

It’s not that people are bad at their jobs or don’t care. It’s that culture is transmitted through observation and osmosis, not through documentation. Across enough managers and interpretations, the culture becomes distorted. The edges get sanded down, the things that made you special start to feel risky or off-brand. Suddenly, you’re optimizing for what feels safe rather than what actually works. Playing not to loseThere’s a scarcity mindset that creeps in as you scale, often without anyone noticing it’s happening. You become afraid of:

So you get conservative in ways that feel responsible but are actually corrosive.

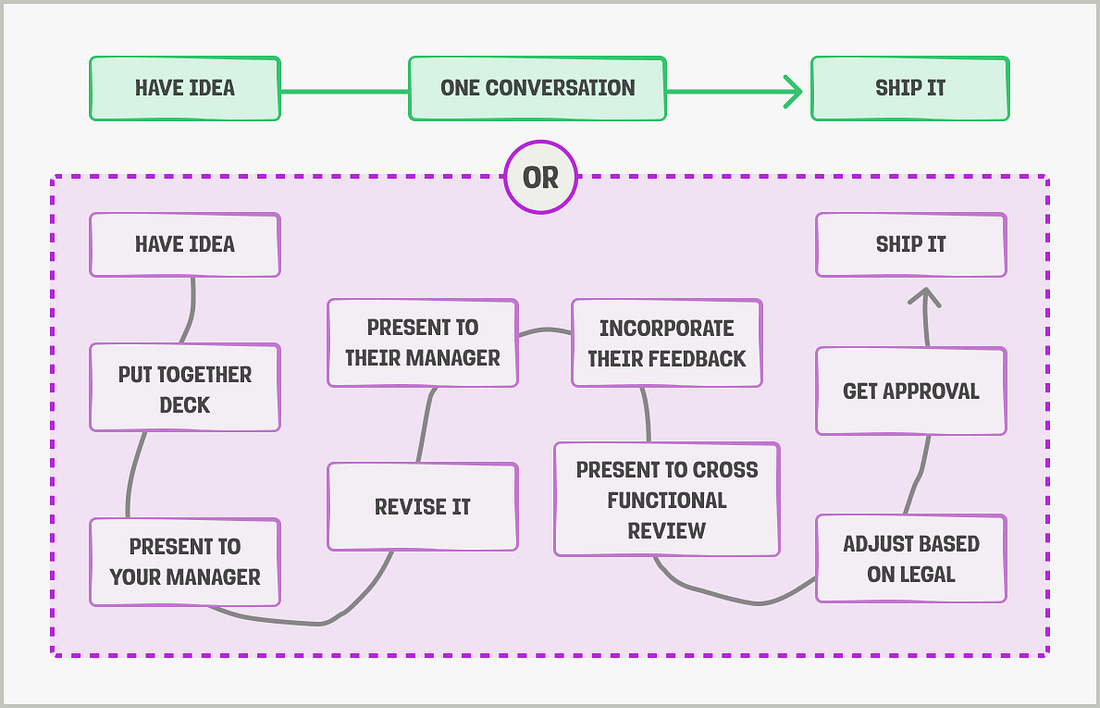

I watched this happen to our process for building products. At the start, we would say “we need to ship this feature,” have maybe one conversation, and get it done. This evolved into a process of pitches, presentations, and approvals: By the time you got to actually building something, the original insight that made the idea good had been committee’d into something safe and unremarkable. The scarcity mindset is insidious because it masquerades as prudence, as grown-up decision-making, as the kind of thing serious companies with serious responsibilities should be doing. But it’s poison. How to avoid this fateThe honest truth is I don’t have a perfect answer. Maybe it’s unsolvable as startups scale. Maybe every company that grows past a certain point loses some of what made it special. But I think there are a few things that matter:

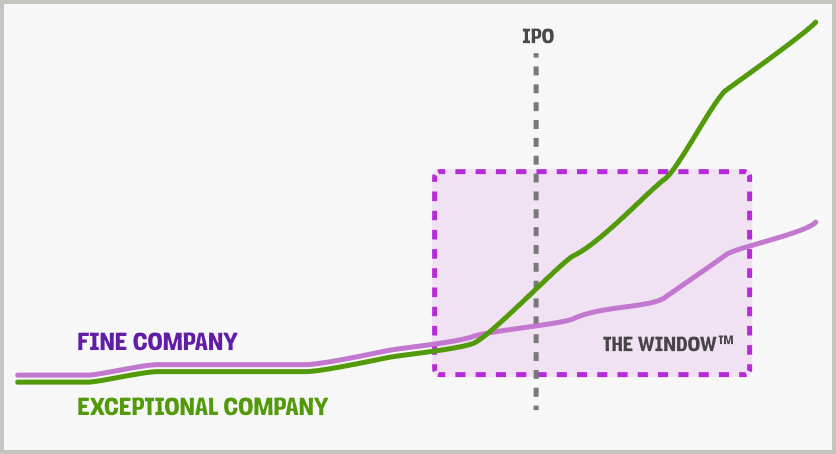

This means your startup is likely going to be messier and more chaotic. It’s not going to be “proper” or “grown up,” but you need to live with it to become exceptional. The real riskFor companies with some success and a good culture, the biggest risk isn’t that they’ll become a bad company or fail outright, it’s that they become a fine company that could have been exceptional. They sand down their edges in pursuit of respectability and become indistinguishable from everyone else. This company is still around and doing good work, but there was a window, a critical 18 to 24 month period, where different decisions could have changed the trajectory entirely. Staying aggressive could have meant 5-10x the outcome. We chose prevent defense and got a respectable result instead of an exceptional one. For companies in this window, the question is whether they’ll recognize when they start playing prevent defense, notice when the “experienced hire” starts to matter more than the culture fit, and catch themselves optimizing for safety instead of for winning. Because in the end, prevent defense doesn’t actually prevent anything other than winning. Written by an anonymous member of the PostHog team, who is also probably one of the only people at PostHog who knows what “prevent defense” is. 🦔💼 HedgejobsWant to help us make that 10x outcome a reality (or just learn who wrote this piece)? We’re hiring product engineers and more roles like: 🛋️ More good reads |

Similar newsletters

There are other similar shared emails that you might be interested in: