How Google Maps caught the train

How Google Maps caught the trainThe story of one rider's wayward subway ride that sparked the idea for Google TransitIn 2005, Avichal Garg was visiting friends in New York City and kept getting lost on the subway. He didn’t know which lines went uptown vs downtown, and local signage wasn’t much help. After boarding the wrong train (yet again) and showing up 45 minutes late to dinner, he’d had enough. At home in the Bay Area, Avichal used Google Maps constantly. So it baffled him: If Google Maps could get him anywhere by car, why couldn’t it help him catch the right train in New York? On his flight home to California, he pulled out his laptop and drafted a product spec for Google Transit. Drivers vs ridersWhen Google Maps launched in 2005, it made waves with its speed, draggable maps, and simple interface. While it felt like a big step forward from MapQuest and Yahoo Maps, it was still built for drivers. But millions of people living in cities like New York, London, and Tokyo didn’t drive. Instead, they relied on subways, buses, and trains. And in 2005, before smartphones and app stores, transit riders still used printed maps and paper timetables. Some transit agencies had websites, but they were slow, clunky, and basically unusable on mobile devices. The visionIn addition to being a frequent Google Maps user, Avichal also happened to be a product manager on Google Search. So when he got back to Mountain View, he shared his idea with a few colleagues. They connected him with Chris Harrelson, a Maps engineer who was exploring alternative routing algorithms for walking, biking, and transit. Avichal and Chris met up and quickly aligned on a vision. Avichal came into work on a Saturday morning and over the next 48 hours, dreamed up something that went far beyond subway directions. He imagined a future vision of Google Maps where a user could say: “I have a conference in New York on June 16 — how should I get there?” Google would ask some clarifying questions (e.g., do you care more about cost or speed?), then return a seamless, end-to-end plan, like:

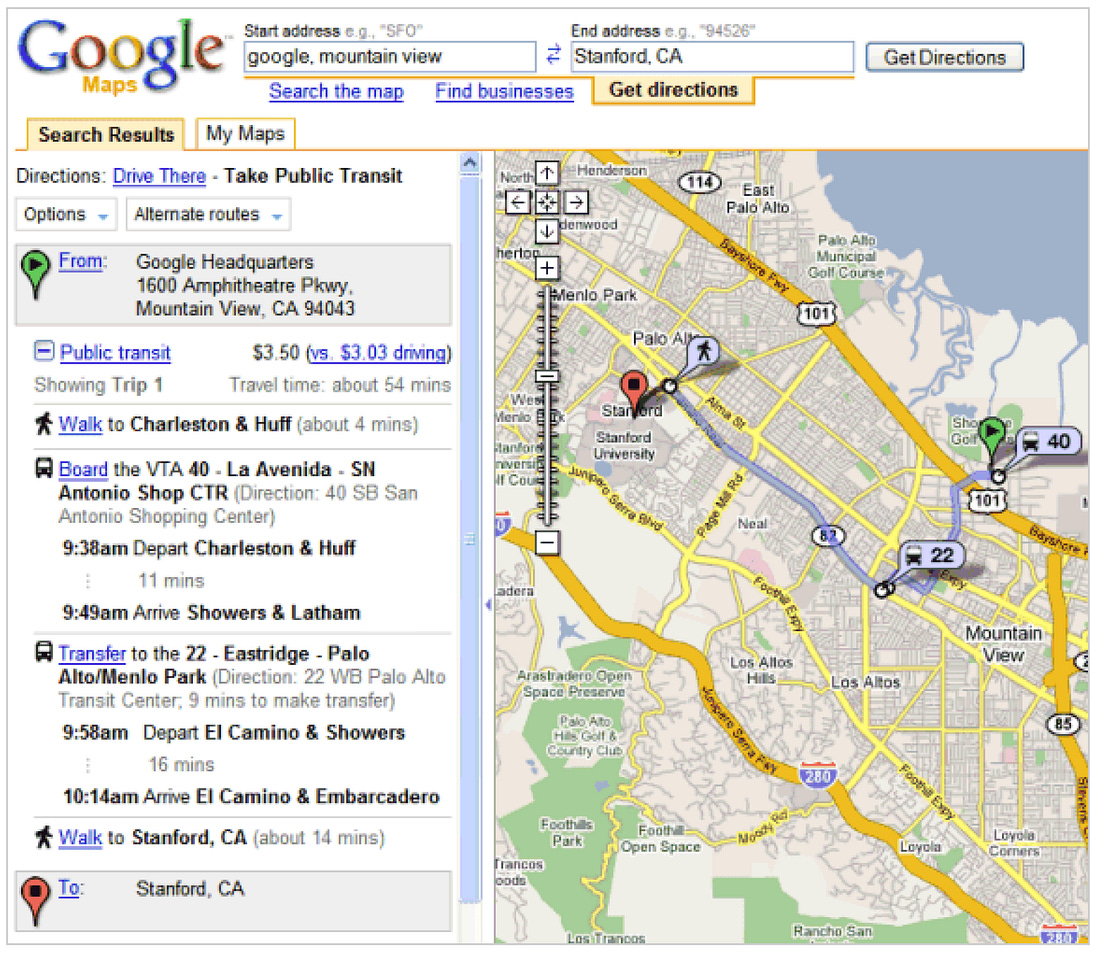

It wasn’t just about directions. It was about understanding intent and guiding someone through every leg of a journey — across cities, systems, and transportation modes. The first versionAt the time, Google supported employees spending 20% of their time building exploratory projects and there was a relatively low bar for launching experiments in Google Labs. So Avichal and Chris got to work. Chris had already gotten transit data from Portland’s TriMet agency, which was one of the first transit agencies to start opening its data. While Chris focused on building routing algorithms, Avichal began selling the vision. He first pitched the idea to the Google Maps team, but they were deep in other projects, and transit wasn’t a priority. So Avichal found internal allies like Katie Stanton, Steph Hannon, Lars Rasmussen, and Leland Rechis, and rallied support from engineers in New York and Zurich. Avichal and Chris leveraged the Google Maps API and, partnering with Portland’s TriMet, launched the first version of Google Transit in late 2005 as an experimental Labs project. Standardizing and scalingTo make it easier to share and import schedules and routes, Google and TriMet co-created a standardized data format: the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS). While this started as a one-off collaboration, it quickly became the standard many transit agencies still use to publish their data. With a common format in place, the next hurdle was adoption. To scale, they needed more transit data, so Avichal turned into a one-man outreach team. He made cold calls, joined panels at transit industry conferences, and convinced agencies to share their data with Google. Smaller cities like Eugene, OR, and Honolulu, HI were quick to join, as they had small teams and were eager to get their data to riders. But the bigger cities were trickier. Cities like New York and Chicago had dedicated web teams with incentives to drive user traffic to their own websites, not to Google Maps. But momentum built. Once a critical mass of smaller cities signed on, Google’s partnerships team stepped in to scale the outreach. The tipping point came in 2007 when Google signed a partnership with New York’s MTA. At this point, Google Maps took notice and decided to fully integrate transit into Maps as a mode for directions. More data started pouring in, including real-time bus and train locations, bike paths, and walking routes. Google Maps became the first large scale mapping product to support directions across multiple modalities (driving + transit). Transit became enough of a competitive advantage for Google Maps that Maps appeared in the app store as “Google Maps + Transit.” The next chapterWhat started as one person’s pain point of getting lost on the subway grew into a global routing system that could map out complex, cross-city journeys with ease. Today, nearly 20 years later, Google Maps helps millions navigate by bus, train, bike, and foot. But wait, there’s more! To hear more about the design decisions behind Google Transit and a see the video interview with Avichal where we discuss the origin of the idea for Transit, subscribe to my Substack. |

Similar newsletters

There are other similar shared emails that you might be interested in: