It's not a principle until it costs you money

- Sergio Visinoni from Sudo Make Me a CTO <makemeacto@substack.com>

- Hidden Recipient <hidden@emailshot.io>

Hi, 👋 Sergio here! Welcome to another free post from the Sudo Make Me a CTO newsletter. If you prefer to read this post online, just click the article title. As this is a free newsletter, I do immensely appreciate likes, shares and comments. That's what helps other readers discover it! It's not a principle until it costs you moneySurprising advice from the advertising industry, where the tech industry seems to be hading to, and why I refused a couple of potentially lucrative gigs. All in one article!I still remember very vividly the moment I heard this for the first time: “It’s not a principle until it costs you money”. I was coming back from one of my morning walks in the woods, listening to a podcast episode in which Cal Newport was interviewing Ryan Holiday. It immediately stuck, and I keep referring back to it when reflecting on past decisions or when approaching new ones. This quote is attributed to Bill Bernbach, one of the co-founders of DDB, an international advertising agency.¹ In 1964, after the U.S. Surgeon General issued a warning about cigarette smoking, Bill Bernbach vowed to keep his agency out of the cigarette business. One of the most profitable advertising categories in those years. That decision cost DDB a lot of money, but he stood by it. I don’t know Bill’s full life story, but if that’s true (and not a made-up internet legend), he earned my full respect and admiration. Hey, in case you missed it, I’m running a special promo during November, called Brain Friday. A few months later, a good friend of mine offered me a slightly different angle on the same underlying concept, citing a famous quote from the Dalai Lama. “Judge your success by what you had to give up in order to get it.” People often focus on the first degree of interpretation, which basically means that to achieve success, you’ll need to make sacrifices. No, this isn't an apology for the 9-9-6 model. But there’s another angle to it, which is far more interesting: what are you willing to give up for your success? Or rather, what are the things you are never going to sacrifice on the altar of so-called success? Are you willing to sacrifice your principles and moral values to become richer? Before you raise your eyebrows and mumble something about this self-righteous dude coming with a moral lesson, let me reassure you. This is not a moral lesson. I’m not here to issue judgments on those who occasionally, sometimes, or even frequently prioritise money over values. Unless you’re either Elon Musk or Sam Altman. Then I definitely can tell you I despise you passionately. But that’s not the point of today's article. The point is instead to share personal examples of me struggling to apply those same principles, and sometimes succeeding. What’s the tech industry’s purpose?I’ve recently rewatched the seminal recent TED talk from Scott Hanselman, going by the telling title Tech Promised Everything. Did it deliver?  What I found highly relatable in his impressive talk is the combination of the insane passion he has had for technology since the early days, and his disenchantment with what the tech industry managed to do, or not do, with it. I share both of them: the early days passion, still alive, and the massive disappointment with the industry that we’re all part of. I’ve covered the leadership aspect of it in one of my recent posts. This one looks at the tech industry more broadly. When exactly did the ethos of the early pioneers who helped create UNIX, the Internet, and the Open Source movement, all of which were genuinely moved by the intention of making technology helpful and accessible, get replaced by the Wolf of Wall Street type of characters who eventually gave birth to the modern broligarchy? When exactly did technology become an instrument for the concentration of power in the hands of the few, while everyone else seems to believe that a world of always-on, no privacy, fake news, and slop content is an acceptable definition of progress and prosperity? Brian Merchant might argue that it all began with the Industrial Revolution, and he’s probably right. But the landscape of modern internet-based technology was very different from today's until at least the early 2000s. When I reflect on Scott Hanselman’s words and look at the state of the planet today, I can’t accept the dominant narrative that naively presents all this as progress, inevitable, and net positive. I can’t help but ask myself: what is the purpose of all this “innovation”? Why does everybody get so worked up about “winning the arms race with China”, as if that were a universal and unquestionable goal for “the Western world”? Why does nobody seem to stop and ask a deceivingly simple question: what should be our key priority as a species? I’ve recently started exploring the world of Wardley Mapping as a key tool to better understand complex systems, and while doing my research on Simon Wardley, I came across one of his recent declarations that I can only subscribe to:

In the same post, he also goes on to say that all the other “problems” caused by GenAI, such as copyright infringement, the induced decline in our cognitive abilities, or the impact on the environment, are just a distraction. I disagree with him on dismissing them as such. While I can agree with a certain hierarchy of problems, I don’t believe lesser problems are just distractions. They can be, if deliberately used to mask the elephant in the room. But that doesn't make them less real, and they are affecting people's lives today. I’ve spent 25 years in the tech industry, and a bunch more than that playing with computers or otherwise programmable systems. Like Scott, I remember when we got our first Commodore 64 at home. I don’t remember exactly I old I was, but I was probably around 10. I remember the first time I installed Linux on a PC, in 1997, and feeling awe toward those mythical figures who devoted their time to creating such a powerful, instructive, and open system that anybody could use and contribute to. I remember getting my first real job in 1999, working for the first (and last) Italian Linux distribution. I was literally living the dream. When I look at where we collectively are now as an industry, some 25 years later, I can’t help but feel that at some point we took the wrong turn in the road. Cory Doctorow captured an important aspect of it when he coined the concept of enshittification, referring to the seemingly inevitable decline in quality of online products and platforms.³ But that doesn’t cover it all. There is another more fundamental problem that has to do with purpose, of which enshittification is just a manifestation. Despite all the efforts of big-tech propaganda in the first two decades of the 2000s, its true purpose is becoming clearer as we progress. We might even credit the Trump administration for allowing it to get rid of its veil of hypocrisy and fully embrace and recognise its true nature, which is perfectly captured by Simon Wardley in his poignant description of what LLMs are. The king is naked, as the old saying goes. Now it’s up to us to decide whether it still deserves a crown. Whether we still want to be ruled by it. Whether we want to contribute to its increasing power over our lives. A tale of saying no, twiceThis is where I get back to the quote that inspired the title of this article. For those who don’t know it, I do work as an independent consultant, coach, and wannabe community builder. The lion’s share of my yearly revenues comes from various types of consulting engagements with companies that need my services. In the last month, I found myself saying no twice to potential new gigs. I’m acutely aware of the difficult job market out there and of the many people who are struggling to find a job. I’m not bragging about the luxury and privilege of being able to decline a contract. Like all of us, I'm navigating a very uncertain field. The reason I refused to engage with those offers has been the same for both cases: they were directly connected with promoting the use of AI-assisted coding tools in software development. I said no because that to me felt akin to selling drugs to teenagers, or optimising algorithms to keep them consuming online content and target them with highly personalised advertising, which is basically the same thing. Except one of them is legal, and the other isn’t. And let me be clear: I do not have any inherent problem with the underlying technology itself. Technology is neutral, and can be a tool to be used (or not) under certain specific circumstances. But the tech industry is not neutral, and it’s increasingly aligned with a world view that I don’t want to actively contribute to realising. Selling AI-related consulting to companies or individuals who are drowning in FOMO is the best definition of easy money you can find on the street in 2025, possibly after selling drugs. Only a fool would give up the opportunity to make that easy money. Or someone who doesn’t want to even accidentally be contributing to the prosperity of an industry so profoundly broken at its core. An industry that, day after day, looks like it needs to be rebuilt from the ground up as the only way to save us all from the dramatic deterioration of our collective lives. I don’t judge those who enthusiastically promote the “inevitable revolution” of GenAI, but I’d love to better understand their motives, beyond the overly individualistic (capitalist) survival of the fittest argument. Or pure and simple personal gains. But please don’t tell me AI will cure cancer and solve the climate crisis, as I still go with the original SRE motto that hope is not a strategy. Definitely don't ask your favorite chatbot to suggest an answer either. We can certainly find better arguments than magical thinking or more slop. Should we do something about it?I recently watched with my two kids one of my favorite Pixar movies, WALL-E. For those who don’t know the movie or have forgotten about it, it’s a story set in a hypothetical future in which humans have basically depleted natural resources on Earth, and fled the planet on a Starship-like space-ship to “wait it out”, hoping that one day the planet might recover so that they could eventually return home. While the movie is willingly depicting an apocalyptic and far-fetched future, it also has a Black-Mirror-esque side to it: an obvious exaggeration of what reality might turn out to be, yet not too unlikely at its core. What I found the best part of it was its representation of what human beings looked like in that prosperous and technologically evolved society.

While the folks at Pixar decided to visually represent it like this… … I invite you to re-read the description above and ask yourself how much our lives have been evolving in that direction over the past couple of decades. And no, while it will definitely help, exercising every day on a treadmill would not be an effective antidote to prevent us from slipping further towards that possible future. Are you familiar with the saying “One dollar, one vote”? The idea is simple: every purchase is a political action. When you give your money to someone selling you a product or a service, you’re implicitly supporting them. Who we give our money to, and who we accept money from, is our biggest lever. That’s why I’ll never buy a Tesla, even though I used to like the cars and what I used to believe they stood for. That’s why I’ll never buy a Starlink connection, even though relying on crowded camping WiFi or poor 4G connections for work when traveling in our motorhome is objectively painful and unreliable. That’s why I don’t want to contribute to the adoption of GenAI-related tools, even in their “helpful” incarnations, and miss out on some lucrative contracts. I’m also aware that not everybody is in the privileged situation of being able to say no. Life is hard, keeping your family alive can be challenging at times when massive layoffs have become news that doesn’t make headlines any longer. I’d like to do more to help bring some sanity back into this whole industry. I have been suggesting the idea of setting up some sort of “Luddites in tech”⁴ online meetup with some fellow practitioners, and many found it interesting. I know I’m not going to go anywhere alone, so this is an open invitation to all my readers. If you share a similar level of disappointment with where this industry is going. If you find yourself lost after years of believing you were working on something meaningful and positive. If you’d like to discuss ideas, strategies, and suggestions on how we could come together and do something about it, please hit me up. Just reply to this email. Share your unfiltered thoughts, and let’s take it from there. The worst that can happen is that we’ll meet some new friends on the journey. Help keep this newsletter freeI love writing this newsletter, and I intend to keep it free forever. If you want to support my work, you can engage with me in one of the following ways:

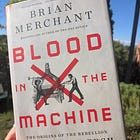

If your needs fall into a different category, such as newsletter collaborations or sponsoring, please reply to this email or schedule a free call via this link. 1 I didn't know about the origin of the quote until I did some online research and found this interesting article. 2 Find the original LinkedIn post here. 3 Read more about it here. He recently published a book of the same title, expect a review in the upcoming months, as soon as I get to it in the growing list of to-read. 4 Before you dismiss the term Luddite as a synonym for retrograde and anachronistic, go read the work of Brian Merchant on the topic. You can find more details in a previous article. Sudo Make Me a CTO is a free newsletter edited by Sergio Visinoni. If you found this post insightful, please share it with your network using the link below. If you or your company need help with one of the topics I talk about in my newsletter, feel free to visit my website where you can schedule a free 30 minutes discovery call. I'd be delighted to investigate opportunities for collaboration! |

Similar newsletters

There are other similar shared emails that you might be interested in: