A Humbling Experience, Lessons Learned, and Adventures in Self-Hosting

- Sergio Visinoni from Sudo Make Me a CTO <makemeacto@substack.com>

- Hidden Recipient <hidden@emailshot.io>

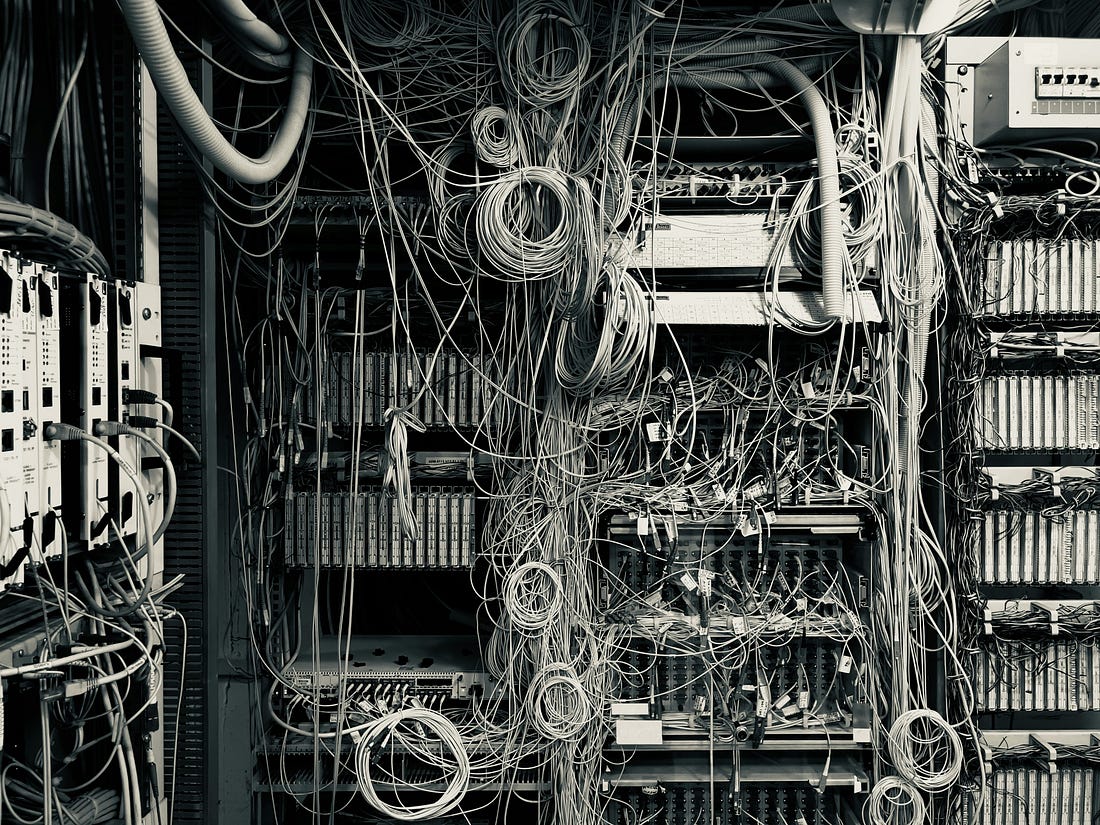

Hi, 👋 Sergio here! Welcome to another free post from the Sudo Make Me a CTO newsletter. If you prefer to read this post online, just click the article title. As this is a free newsletter, I do immensely appreciate likes, shares and comments. That's what helps other readers discover it! A Humbling Experience, Lessons Learned, and Adventures in Self-HostingHow a recent hubmling experience helped me identify a major gap, and why I'm going all in with self-hosting my own services.Today’s issue covers to different topic. The first one is a reflection on a recent humbling experience that made me reflect on following our own advice and being human. The second is an update on recent investments in self-hosting, why I think it matters, and why now. A Humbling ExperienceAn important part of my work has to do with offering advice. I advise companies on their tech strategy, tactical decisions, organisational setup, hiring, etc. I advise individuals in coaching and mentoring sessions on a broad set of topics: from distilling strategy to making tactical decisions, from preparing for interviews to becoming more effective in their job, etc. I advise members of the Sudo Make me a CTO Community on very similar topics, and all participants do the same with each other. You could consider it a community for distributed advice, or an advice mesh, to use a fancy word. Advice, though, is a weird and sometimes dangerous beast. The conventional wisdom about the subject tends to gravitate towards certain beliefs. A common one is that someone who's advising on a topic - no matter the subject - must be an absolute beast at it. An insidious corollary is to believe that someone can only advise on a topic if and only if they're absolutely perfect in the field. As humans, we're very effective in pointing the finger at behaviours that are inconsistent with stated messages. When that happens, we're resorting to the old do as I say, not as I do saying. Granted, there is a good bunch of folks out there that are outright incompetent or hypocritical, and such behaviours should be called out appropriately. There is no justification for deliberately being a bad person. But the majority of people are just humans, with their desires and limitations. They're striving to become better day after day, and often struggle to get there. Getting better is hard. Changing our deeply rooted automated mechanisms is hard. Keeping a cool mind in difficult and stressful situations is hard. In essence, learning a new skill is hard. Any new skill. Particularly those that require changing deeply rooted behaviours or beliefs. Humans are also weird creatures: we're inconsistent, incoherent, and equipped with lousy memory, all the while we try to convince ourselves that we're mostly rational creatures¹. As such, though I know many people who excel at various disciplines or skills, I don't think I've ever met anyone who could be considered perfect: someone always doing the right thing, never making a single mistake. Funnily enough, modern times’ "godlike" human creations, believed by some to be omniscient and always right², are flawed in the same way: they're non-deterministic, erratic, and make mistakes on topics they're supposed to master as they were part of the training dataset. What I believe truly differentiates highly effective people from the rest is not a 100% score in consistency. It is their ability to recognise when they're not behaving in accordance with their own advice, acknowledge it, and do something to address the issue. A perfectionist would likely be consumed by anxiety and a sense of guilt, and either work themselves to death or give up completely as a consequence. An ambitious, highly effective person is instead capable of cutting themselves some slack first, acknowledging the inherent imperfection of human nature, and then calmly reflecting on what to do next. How to prevent the same slippage from happening in the future. What lessons can be drawn from the experience? How to leverage them in the future? This is exactly what happened to me recently: I failed at something that I've been repeatedly advising people on. Details aren't super important, but I'll give you some context. In an intro call around a potential opportunity for collaboration with a company that is expanding into the fractional CTO business, I was asked to describe a couple of cases in which there had been a clear "before and after you", as they said. Before I realised it, I went into a relatively long description of impact from a technological perspective: improvements, structure, strategy, etc. Until the person I was talking to very politely interrupted me and noticed how those details would not be relevant for a CEO, who would be looking to hear about business impact, metrics, etc. Bang! I immediately felt like crap. How could I have made such a rookie mistake, one that I regularly recommend others to dodge and prepare for? I felt so embarrassed. Realising that I was failing at such a basic task was like putting gasoline on the fire of my internal monologue. The conversation with that other person moved on and eventually came to an end, but I spent the rest of the day and part of the night ruminating about what had happened. The question that kept spinning in my head was: why did I fail at such a basic task? I came up with many explanations, all of them converging toward the same root cause: I had not prepared at all for that call, and instead, I tried to wing it. I came in with the wrong expectations, thinking it would be an easy chat, and trusted my ability to improvise. I didn't invest the necessary amount of time to clarify my own expectations from the meeting and the messages I wanted to send. That's the key learning, and this is what I'll do next. On the one side, I'll be more selective about the intro calls I accept, as I tend to accept them all by default. This promotes a low-stakes and sometimes condescending attitude that I intend to eradicate. In parallel, I'll ensure I spend a decent amount of time preparing each and every intro call I'll accept going forward, and script answers to what emerge as the most common topics or questions. That embarrassing call turned out to be a gift in disguise, as it allowed me to identify what had been a dangerous blind spot until that moment. Adventures in Self-HostingI've been upping my game in self-hosting lately, something that has been raising some eyebrows at home. For those unfamiliar with the term, the concept is straightforward: it's the practice of hosting applications on your own servers as opposed to using SaaS or Cloud applications. While I already had a bare setup with Home Assistant to control and automate my house, I'm now moving into setting up refurbished enterprise-grade equipment for servers and the network. Two main reasons justify the move: the geopolitical context and a general enshittification³ of online products. But interest and fun are a powerful cherry on top. Geopolitical instabilityI was born in the late seventies and grew up in the eighties and nineties. I remember thinking naively that with the end of the Cold War, opposing the eastern and western blocs, the subsequent demise of the Soviet Union, and the promises of democracy and access to information offered by the nascent Internet, the future looked brighter than ever. That the new millennium would see humanity move to a superior level of maturity, one dominated by peace and harmony. Twenty-something years later, I must admit I was not only wrong, but even borderline insane. Today's world is messy at best. I won't go into details as I don't see the point of stating the obvious. The only silver lining is that, as someone who has always appreciated the Sci-Fi genre, I now have the luxury of living in a dystopian, futuristic world dominated by demagogic leaders and mega corporations 24/7. I'm still debating whether that's a net positive or net negative. That said, given that ninety-something percent of the online services I use are US-based, a country that seems willing to sacrifice anything on the altar of the AI race, including users’ privacy and creators’ copyrights, I strongly feel I need a resiliency plan. This plan entails finding alternatives to all those services, where often the best tradeoff is going the self-hosted route. Product enshittificationUser experience is on a constant downward trend. The stubborn insistence on sprinkling AI chatbots and allegedly smart features into every single product is so annoying it's not even funny anymore. It's Clippy all over again⁴, except this time it's not enough to pick a sane operating system to escape the madness. Compound that with constant price increases driven either by tariffs or the need to improve profitability, often both, and we're probably witnessing peak-enshittification of online services. Self-hosting will allow better control of the services I use, reduce vendor lock-in, and increase flexibility in selecting the features I want to enable and use. Granted, this comes at a cost, as it does, giving up control of your working tools to entities with very different incentives than yours. Interest and funFinally, I love this stuff. In a previous life, I have been deeply involved with running my own services, open source projects and communities, and building or tinkering with software in my free time. That's how I got involved with this industry to begin with. When I first got involved, it wasn't to chase fame or fortune, as back then, tech was still largely unfashionable and a nerdy thing. I got involved because I loved understanding how machines worked and communicated with each other. I loved the ethos and principles of the open source community, way before GitHub existed. The busyness of life and work led me to slowly drift away from that world. I recently started to realise how much I have been missing it. The biggest advantage today, compared to twenty years ago, is the amount of high-quality information available to educate oneself on all these topics, be it networking, filesystems, virtualization, or programming languages. After years of focusing on the user and business-facing aspect of the stack, I want to go back to understanding the underlying layers, which are often abstracted away in today's most common ways of building software. In fact, it might just be that the grandiose principles and values mentioned earlier are just an excuse to play with machines again. I'd still be OK with it if it turned out to be the case. Help keep this newsletter freeI love writing this newsletter, and I intend to keep it free forever. If you want to support my work, you can engage with me in one of the following ways:

If your needs fall into a different category, such as newsletter collaborations or sponsoring, please reply to this email or schedule a free call via this link. 1 The well-known best-selling book by Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow, is a fascinating journey into exploring the fallacies of the human mind. When I first read it, it blew me away, and had this weird effect of making me feel both more and less stupid than I thought. More, as it highlighted the common fallacies I too fall for. Less, because it made me realise it's a generalised issue, not something specific to myself, and it equipped me with tools to identify it more effectively. 2 In case you missed the last 3 years of FOMO, hype, hysteria, and positive contribution to carbon levels in the atmosphere, I'm talking about LLMs and their various incarnations. 3 In case you never heard it, the relatively new term refers to the progressive decline in quality for online commercial products. Find out more on the Wikipedia page dedicated to the concept. 4 If you're too young to remember Clippy, I might envy you. In essence, it's been a failed attempt at making computers “smarter” across Microsoft products of the early 2000s. I particularly love this snippet from the Wikipedia page dedicated to the subject: “According to Alan Cooper, the "Father of Visual Basic", the concept of Clippit was based on a "tragic misunderstanding" of research conducted at Stanford University, by Clifford Nass and Byron Reeves, showing that people treat computers as social actors – responding with emotional and social responses as if they were other human beings and thus is the reason people yell at their computer monitors. Microsoft concluded that if humans reacted to computers the same way they react to other humans, it would be beneficial to include a human-like face in their software. As people already related to computers directly as they do with humans, the added human-like face emerged as an annoying interloper distracting the user from the primary conversation.” Sudo Make Me a CTO is a free newsletter edited by Sergio Visinoni. If you found this post insightful, please share it with your network using the link below. If you or your company need help with one of the topics I talk about in my newsletter, feel free to visit my website where you can schedule a free 30 minutes discovery call. I'd be delighted to investigate opportunities for collaboration! |

Similar newsletters

There are other similar shared emails that you might be interested in: