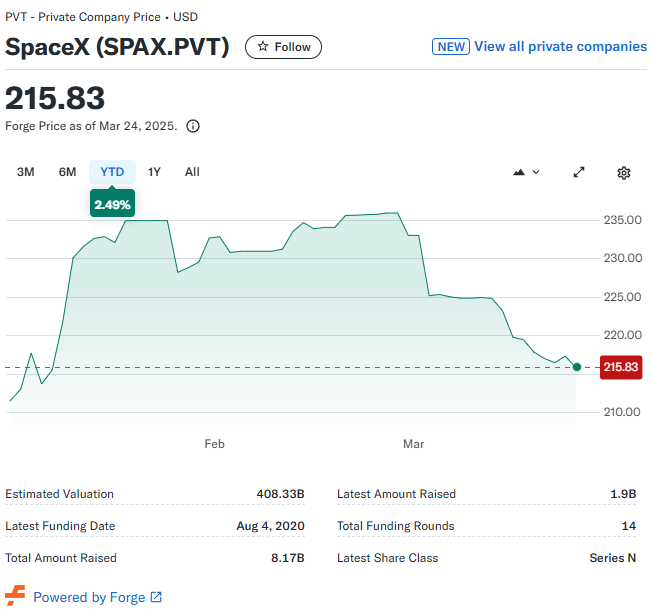

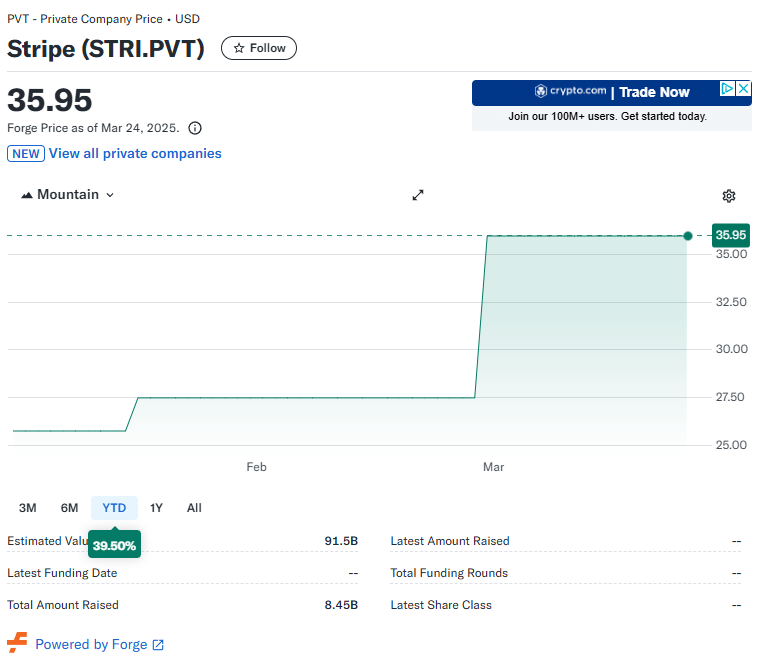

Private markets are the new public markets | Oh man here’s a SpaceX stock chart:  Source: Yahoo Finance. That’s a year-to-date chart of SpaceX’s price reported by Forge, a private stock marketplace, as shown on Yahoo Finance. Here’s Stripe’s considerably more boring chart:  Source: Yahoo Finance. That chart shows only two price changes (from $25.77 to $27.50 per share on Jan. 17 and from $27.50 to $35.95 on Feb. 28), suggesting that it might reflect two trades. Or fewer: Yahoo adds a note explaining that the “Forge Price is a derived data point that reflects the up-to-date price performance of venture-backed, late-stage companies. Forge Price is calculated based on a proprietary model incorporating pricing inputs from publicly-available primary funding round information, secondary market transactions and indications of interest on Forge and other private market trading platforms.” [1] Here’s OpenAI’s chart, which is even flatter. SpaceX and Stripe and OpenAI are of course private companies; you can’t buy them on the stock exchange. But they are big private companies with lots of shareholders (employees, early investors, etc.), and some of those shareholders have been able to sell their stock, and there are markets for that stock. The Wall Street Journal reports: It is getting easier to invest in high-risk, high-reward private companies. Now, all it takes is $5,000 to buy a stake in a firm like SpaceX or OpenAI. EquityZen and Forge Global, which are marketplaces for trading shares of private companies, are lowering the minimum investment from tens of thousands of dollars, the firms plan to announce Tuesday. They are doing so as part of a partnership with Yahoo Finance, in which they also share their data on roughly 100 pre-IPO companies on the website. This is the investment industry’s latest play to put nonpublic companies in the hands of individual investors. Until recently, investing in private companies was the domain of institutional investors and ultrawealthy with the capital and connections to participate in fundraising rounds. Those often require seven-figure minimum investments and decadelong lockups. I guess the way to think about it is that there are increasingly three tiers of public-ness: - Public companies. These file public financial statements with the US Securities and Exchange Commission and are usually listed on stock exchanges. [2] Anyone can buy them through their broker’s website or app, generally paying commissions of $0. Their stocks trade constantly, and if you want to sell your stock you can hit a button on your brokerage app and the stock will be gone in less than a second.

- Private-is-the-new-public companies. These do not file public financial statements and don’t sell their stock to the general public. But they trade on platforms like Forge and EquityZen, with varying frequency: Just from looking at the charts, SpaceX seems to trade a fair amount, Stripe considerably less. Not everyone can buy them — you need to be an “accredited investor,” which “means earning $200,000 annually (or $300,000 for couples) or having a net worth over $1 million” — but that threshold is low enough that it is roughly equivalent to “having a brokerage account.” Also the minimum investment is higher: You can buy a share of Tesla Inc. for about $280, and many brokerages will let you spend even less for a fractional share, but Forge and EquityZen won’t let you buy less than $5,000 of SpaceX. Also “Forge and EquityZen charge commissions between 2% and 5% on each transaction.”

- Truly private companies, which don’t trade. Their stock is owned by a small group of people who know each other — the founders, maybe one or two outside investors, etc. [3] — and those people don’t sell. (Perhaps the terms of their investment don’t allow them to sell, or perhaps there are only one or two of them and it would never occur to them to sell.)

The boundary between Categories 2 and 3 is porous: If you start a company in your garage with your buddy and each of you own 50%, your stakes will not trade on Forge; if you then raise some seed money, they still won’t; but there is some point — some round of venture capital, some number of former employees — where you will start to lose your personal connection to every shareholder, and they’ll start putting their stock on these trading platforms. And one day you’ll wake up and your stock price is on Yahoo Finance. The boundary between Categories 1 and 2 was historically important: To become public, a company had to do an initial public offering, filing documents with the SEC and hiring banks to sell their stock broadly to investors. But that boundary is blurring. If you can raise lots of money privately, and your shareholders can get liquidity whenever they want, and your stock price is public, you might care less about filing the paperwork to officially go public. Still there is at least a difference of degree between public and private-is-the-new-public companies. When companies do initial public offerings, the rule of thumb is that they tend to sell about 10% to 20% of their stock to the public, and more of it starts trading in the months and years after the IPO. Most public companies’ floats — the shares actually available to trade — are fairly large, and they trade a lot. With private companies, even SpaceX, that is less true. Most of the stock is still pretty closely held by the founders and employees and venture capitalists, and only a relatively small amount trickles onto markets like Forge or EquityZen. Block Inc. (formerly Square) is a $39 billion payments company listed on the New York Stock Exchange; between 9:30 and 10:30 this morning, 656,281 shares traded in 3,797 different trades at 150 different prices between $62.18 and $63.69. [4] Stripe Inc. is a $91.5 billion (according to Forge!) payments company that is still private; this year, it has traded (maybe?) at a total of three different prices between $25.77 and $35.95. If you decide to buy some Block stock, you will probably be able to (1) get it (2) in a second (3) at a price within a few pennies of its last trade. If you decide to buy some Stripe stock, none of those things is necessarily true. Also, with a tiny float and infrequent trades, it is not clear that the trading price reflects the “real value” of a company. We have talked about the retail demand for hot private companies like SpaceX and Stripe and OpenAI: There is a lot of demand and not much supply, so there is an ecosystem of vehicles that charge high fees to get access to shares. Presumably if retail investors can get their hands on a few shares directly, they will have to pay up for them. It’s possible that the valuation for $5,000 worth of OpenAI shares for retail-investor bragging rights is different from the valuation for $500 million of primary capital that OpenAI raises from investors. If you are a private company, is this annoying? It used to be that large private companies’ stocks traded on secondary platforms, sure, but their stock prices were not readily available and nicely charted. Investors in private companies might keep track of those prices, and everyone else might occasionally read news articles mentioning things like “SpaceX shares recently traded on private secondary markets at prices implying a $408 billion valuation.” But now there is a widely available public version of that; any time you like, you can go look at a SpaceX stock chart. Does the chart reflect SpaceX’s actual market capitalization? Ehh, one could quibble, but the important point here is that it is a line on your computer screen. If one reason to stay private is to avoid the public pressure and spectacle of a stock price — to avoid focusing too much on day-to-day fluctuations in the stock price — then this undermines that case. Not that Stripe has much in the way of day-to-day fluctuations, yet.  | | | People like to borrow money to buy stocks. In particular, they like to borrow money to buy the S&P 500 index. Intuitively, the safer and more “normal” an asset is, the more tempting it will be to borrow money to buy it and juice your returns. The S&P 500 is the US stock market, so it feels very safe and normal, and lots of people want to borrow money to buy it. There are two main ways to borrow money to buy the S&P 500: - Borrow money from someone and use it to buy the S&P 500. (Buy all the stocks in the index, or buy an index ETF.)

- Buy S&P 500 futures, which give you economic exposure to the price of the S&P 500 index, but don’t require you to put up all the money. Using futures, you can buy about $291,000 of the S&P 500 and put up only about $15,800 of cash: Effectively you pay 5% of the price of the index and borrow the rest. [5]

These trades are roughly equivalent, [6] so you should expect them to be arbitraged and priced about the same. Buying S&P 500 futures is roughly “borrowing money to buy the S&P,” and the price of the futures should reflect the cost of borrowing that money. Who borrows money to buy the S&P? One fun category is leveraged exchange-traded fund investors: You can buy an ETF that offers you 2, 3 or more [7] times the daily returns of the S&P 500; intuitively this is “borrowing money to buy the S&P” but often it uses futures. Others are asset managers or hedge funds who want to be long the S&P 500 without putting up too much money. (For instance, “portable alpha” strategies involve buying futures to get your index exposure, and then using the rest of your money to try to get a little extra return elsewhere.) Who lends them the money? Traditionally, banks and other securities dealers. A bank has customers, they want financing for their stock positions, the bank provides the financing. This is a big business — equity financing, prime brokerage, synthetic prime brokerage, delta-one, stuff like that — but it is also a risky business, [8] and these days heavily regulated banks are not always keen to use their balance sheets to lend money to help people buy stocks. And so it is unusually expensive right now to borrow money to buy stocks. [9] Bloomberg’s Yiqin Shen reports: So-called financing spreads on S&P 500 Index futures — a cost embedded in the price of derivatives that allow investors to gain exposure to stocks without buying shares outright — have climbed markedly during the recent bull market. They spiked to a record late last year and have remained above historical levels even during the latest downturn. It’s happening as equity financing plays an increasingly crucial role in the market, with hedge funds and other big-money players making bets that seek to ride momentum without tying up too much capital. By using futures, they can achieve similar market exposure without paying the full price upfront. In return, they pay a risk-free interest rate plus a financing spread to firms providing the leverage. As more and more players have entered that trade, those spreads have widened, ratcheting up costs. “The dislocation is very large compared to the spread’s historical range, and the S&P 500 is one of the most canonical, most liquid markets in the world,” said Ashwin Thapar, head of multi-asset class investing at D. E. Shaw Investment Management, in an interview. “So the fact that you have seen a spread this wide in the market is especially interesting and relevant to a lot of people.” Thapar contributed to a white paper on the subject, which was published in January. The D. E. Shaw white paper notes that “On the demand side, we have seen unusually strong interest from asset managers in long S&P 500 futures exposure,” in part because of “more bullish sentiment on U.S. equities relative to other regions,” which is maybe less true now than in January. But the spreads are still high. And: On the supply side, dealers are an important source of financing for S&P 500 positions but face an important constraint: the aggregate size of the banking sector’s balance sheet is relatively fixed over shorter horizons. … Moreover, in recent years banks have become more constrained in financing (especially directional) equity exposures. Among other considerations, that is because banks need to optimize their balance sheets given competing regulatory requirements and constraints. Equity financing tends to be balance sheet-intensive and thus can be unattractive for banks.

So the story is essentially that people want to borrow money to buy the S&P 500, but banks are reluctant to lend it to them. This is all done synthetically — it’s not really borrowing and lending money to buy the S&P 500, but rather buying and selling S&P 500 futures — but it comes to roughly the same thing. [10] And because there is a lot of demand and less supply, the rates are high. I feel like we talk about this a lot? It is, a little bit, the story of private credit: Banks are more capital-constrained and reluctant to lend (to leveraged buyouts, etc.), so other lenders with longer-term locked-up money are getting into the lending business. Similarly here you could imagine a story like “long-term asset managers might want to get into the business of lending people money to buy stocks, because the returns are good and banks are constrained.” D. E. Shaw imagined it, writing that “supply could come from sources outside of dealer balance sheets — unlevered investors looking to deploy unencumbered cash might step in to finance equity exposures, given the attractiveness of the S&P 500 futures spread relative to other common uses of cash (e.g., investment grade credit).” That is: Lending money to stock speculators via futures might be pay better than buying investment-grade bonds, so maybe some investors should do it. And it’s happening. Shen writes: “For someone who can provide their balance sheet to the market, they could get a very good rate of return on that position with relatively little risk,” said Paul Woolman, CME’s global head of equity products. ... Janus Henderson is among those taking advantage of the wider financing spreads. Natasha Sibley, a manager on the firm’s multi-strategy team, said Janus Henderson is buying the stocks in the S&P 500 index and selling futures against them. This so-called cash-and-carry arbitrage is paying off nicely now. “The pickup of equity financing spreads make this trade extremely attractive right now,” Sibley said in an interview. “It has been a popular play among sophisticated real-money investors, such as pension funds and sovereign wealth funds, those with cash to put to work.” If you have cash, you can lend it to stock investors, though the way that works in practice is that you buy the stocks and then you sell the investors the futures. It’s like a synthetic money market investment, and right now it pays. The classical stereotype of retail investors is that they are greedy when others are greedy and fearful when others are fearful: They buy stocks when they see that stocks have been going up, and sell stocks when they see that stocks have been going down. This is, on average, a bad idea — you should buy stocks before they go up, not after — and so retail is widely thought of as dumb money and a contrarian indicator. The famous story is that Joe Kennedy sold all his stocks when his shoeshine boy started giving him stock tips: When the last dumb-money investor is buying, it is time to sell. And so I sometimes say that “one of the best services a retail broker can provide is not answering the phones during a crash,” because stereotypically, when the market crashes, retail customers call their broker at the bottom to say “sell everything!” But this, I think, is less true than it used to be. Retail investing in the US has become more social and meme-driven over the last few years, as retail investors learn about trading from their peers on social media. Some of this reinforces the stereotype: One important investing meme was “GameStop Corp.’s stock has gone up a lot for no reason, so of course it will go up even more for no reason”; retail investors probably did pile into GameStop at the peak in 2021. [11] But another important investing meme is “buy the dip,” and these days retail does a lot of that. The Financial Times reports: Net inflows from retail investors into US equities and exchange traded funds have registered $67bn in 2025, down only slightly from the $71bn spent in the final quarter of 2024, according to data provider VandaTrack. The powerful influx underscores how individual investors remain upbeat on Wall Street equities despite intense turbulence this year, triggered by the president’s erratic tariff plans and the emergence of Chinese artificial intelligence start-up DeepSeek. “Dip-buying has been an essentially foolproof strategy for four of the past five years,” [12] said Steve Sosnick, chief market strategist at Interactive Brokers, a platform widely used by individual investors. He added: “Doing something that works remarkably well for so long means you’re conditioned to stick with it.” A user on Reddit’s Wall Street Bets discussion board, which is popular among amateur investors making speculative bets, offered a similar sentiment: “respect the dip, be the dip, BUY THE DIP!” they said. … Goldman Sachs data shows retail investors have been net sellers of US stocks in just seven sessions this year, despite the S&P 500 having fallen on 25 days. In contrast, big investors tracked by Bank of America made the “biggest ever” cut to their US equity allocations in March. Some people are still stuck in the old ways: Still, some institutional investors and Wall Street analysts regard surging retail demand as a counter-intuitive reason for caution. Aleksander Peterc, an analyst at Bernstein, said: “Back in 1999, when my housekeeper started to ask which stocks she should invest in, that is exactly when things started to fall apart.” Right no in 1999, when your housekeeper asked you for stock advice, she wasn’t on Reddit reading posts about “respect the dip, be the dip, BUY THE DIP!” The retail approach has changed. Though it is plausible that some a meta-version of the original stereotype still works, something like “when the Redditors are telling you to buy the dip, buying the dip has peaked.” I want to follow up on two things that I wrote about yesterday. First, I wrote about Endeavor Group Holdings Inc., which was acquired yesterday by Silver Lake for $27.50 per share in cash. Endeavor’s stock closed at $29.25 per share on Friday, on heavy volume, which was a little weird: Everyone who bought the stock at $29.25 on Friday got cashed out, as promised, at $27.50 on Monday. Why? I discussed several possible explanations, but the consensus seems to be that the correct one was my third explanation: You could bring a shareholder class action against Silver Lake and Endeavor for breaching their fiduciary duties to shareholders, and maybe a court would agree with you and force Silver Lake to pay more. This sort of lawsuit can lead to repricing the deal for everyone.

This deal is controversial for reasons that we have discussed, reasons that are both procedural (Silver Lake is the controlling shareholder of Endeavor and outside shareholders had no say over taking the deal) and price-related ($27.50 seems pretty low compared to the value of Endeavor’s biggest asset, a stake in publicly traded TKO Group Holdings Inc.). And there is a history of successful shareholder litigation against deals like that: In 2022, for instance, the controlling shareholders of Dell Technologies Inc. (including Silver Lake) agreed to pay $1 billion more to cash out shareholders of Dell’s VMWare Inc. tracking stock. So if you paid $29.25 for Endeavor stock on Friday, you were buying (1) a share of stock worth $27.50 plus (2) a share of a class-action lawsuit with a market price of, apparently, $1.75. One reason to do that is that you thought the lawsuit was worth at least $1.75 and wanted in on it. Another reason to do it, though, might be that you were short Endeavor stock (because it was trading above $28 and would turn into $27.50 on Monday), and you decided you wanted out of the lawsuit. Because, as a technical matter, if the lawsuit succeeds and the Endeavor deal gets repriced, people who were short the stock at the closing of the deal — and who paid $27.50 to close out their short at closing — will owe the extra money to their share lenders. We talked about this dynamic in the Dole Food Co. deal: Dole’s controlling shareholder bought it too cheaply, years later a Delaware court ordered him to pay more to the former shareholders, and former shareholders submitted claims for more than 100% of the stock. Why? Partly because there were short sellers, so people really did own more than 100% of the stock. (If short sellers borrowed 10% of the stock and sold it short, then the people who loaned them the stock and the people who bought it from them both owned 10% of the stock and were entitled to the extra money, so a total of 110% of the stock was owned by someone — but short sellers owned negative 10%, so the books balanced.) To make things work out, the short sellers have to pay the extra money, years later, when the lawsuit is finished. This is practically rather difficult — a lot of Dole short sellers complained about being asked for money by their brokers, and others presumably changed brokers or went bankrupt or died in the interim and never got asked — and you could imagine some Endeavor short sellers on Friday thinking “this isn’t worth it, I’m gonna get out before closing.” The other thing that I wrote about yesterday was litigation finance, and in particular the dream of one day having liquid complete markets for legal claims. (The things are obviously related: Arguably there was a market for Endeavor legal claims last week, and it closed at a price of $1.75 per share.) I wrote: It is fun to imagine what a truly complete and liquid market in litigation claims would look like. … What if there were public real-time market prices for every lawsuit? (Or at least, for some mass tort lawsuits and high-profile commercial disputes?) Why bother with the trial? “I see our lawsuit is trading at a market capitalization of $15 million, want to settle for that right now?”

In a footnote I added: Or: Let’s say you have sued me for $100, your lawsuit claim is trading at $10, and I think you’re going to win. Should I go buy up all the claims? That way I lock in my cost: I pay $10 for the claims, you win, you get awarded $100, I pay you $100, and you turn around and pay the $100 back to me; I am only out my original $10. ... Is that … insider trading? Should that be illegal? Encouraged?

A reader suggested a combination of those two points, “complete markets for lawsuits” and “short selling can mean that you own more than 100% of the outstanding shares of something.” The combination is: Let’s say you have sued me for $100 and your lawsuit claim is trading at $10. I go and buy up 120% of the claims, for $12, buying some from holders of the claims and others from short sellers. (I don’t think you can currently sell lawsuit claims short in any meaningful way, but a really complete market would let you!) And then I come to you and say “you know what, you’re right, I give up, here’s your $100.” You pay the $100 to your claims buyers, which means to me, so I get my $100 back. And the short sellers who sold me some extra claims owe me another $20. Losing the lawsuit is profitable for me. This is probably how some amount of credit trading works. If a company puts up an online job posting for an accountant, and the posting describes the ideal candidate as an “ambitious and self-reliant” worker who “develops creative and innovative solutions to problems” and “thinks outside the box,” is that company more likely to restate its financial statements in five years than one that advertises for an accounted who “thinks methodically” and is “grounded and collaborative”? Here are a paper on “Seductive Language for Narcissists in Job Postings,” by Jonathan Gay, Scott Jackson and Nicholas Seybert, and a related blog post by Gay, that … don’t quite answer that question but at least suggest directions for future research? As behavioral researchers in accounting, we are interested in executives who bend the rules. We decided to study job postings after noticing that the language used to describe an “ideal candidate” often included traits linked to narcissism. For example, narcissists tend to see themselves as highly creative and persuasive. … We compiled two sets of terms commonly used in job postings. We call the two sets “rule-follower” and “rule-bender” language. ... Through a series of experiments, we found that rule-bender language attracts individuals with higher levels of narcissism for accounting-specific jobs, as well as other industries. We also found that recruiters are more likely to use rule-bender terms when hiring for highly innovative, high-growth companies. For accounting positions, recruiters are more likely to use such terms when aggressive financial reporting could benefit the firm. Yes right you can see how an accountant who thinks outside the box would be very attractive to a certain set of companies, and how the US Securities and Exchange Commission might be very curious about exactly that set of companies. Wealthy Americans seek refuge from Donald Trump in Swiss banks. Canadians Sign Up for 1,461-Pack of Beer to Get Through Trump’s Term. Bezos-Backed Vertical Farming Startup Plenty Files for Bankruptcy. 23andMe’s Bankruptcy Puts 15 Million Users’ DNA Info on Auction Block. Business Schools Are Back. In Today’s Upended Office Market, the Park Avenue Mystique Endures. Australia’s Gold Road Rejects $2.1 Billion Takeover Offer From Gold Fields. Dropbox Faces Pressure From Activist Investor to End Co-Founder’s Control. Activist Investor Meister to Join Illumina’s Board. “What we’re seeing is how little backbone there is among law firms.” Senior Assassin. If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! |