Users Innovate. Builders iterate.

A few months ago, I got an email that initially looked like spam. The subject line was misspelled and the introduction felt generic, but something about it made me keep reading. I googled the sender, looked at his Wikipedia page, and checked the sent-from URL. Turns out the email was legit — and was from Eric von Hippel, a renowned MIT professor who spent his career studying innovation. Eric developed the theory of “lead user innovation:” the idea that most breakthrough innovations start with users — not designers or engineers. Users who face a real need hack together their own solutions. Then, “producers” (designers, engineers, PMs) come in to refine, polish, and scale those ideas. Eric and his colleagues have documented tons of examples, including mountain bikes, personal computers, and 3D printers.

This made me flinch. I’ve spent my career at the cutting edge of design and technology, helping shape early versions of products like Google Maps, Search, and YouTube. Surely that counts as innovation? But Eric pushed me: “Can you name a time you designed a truly new behavior? Not a better version of something people were already doing — something genuinely novel.” I couldn’t… Rethinking What Counts as InnovationEric’s question rattled me. Had I spent the last two decades just…optimizing? But the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. Most of what we call “innovation” is actually just improving the behaviors humans have always done, like communicating, trading, and navigating. Walking → Horse-drawn carriages → Early cars → Modern cars. Even Waymo’s driverless cars are just one step in a long line of ever-evolving transportation tools. The same pattern shows up in tech. Consider:

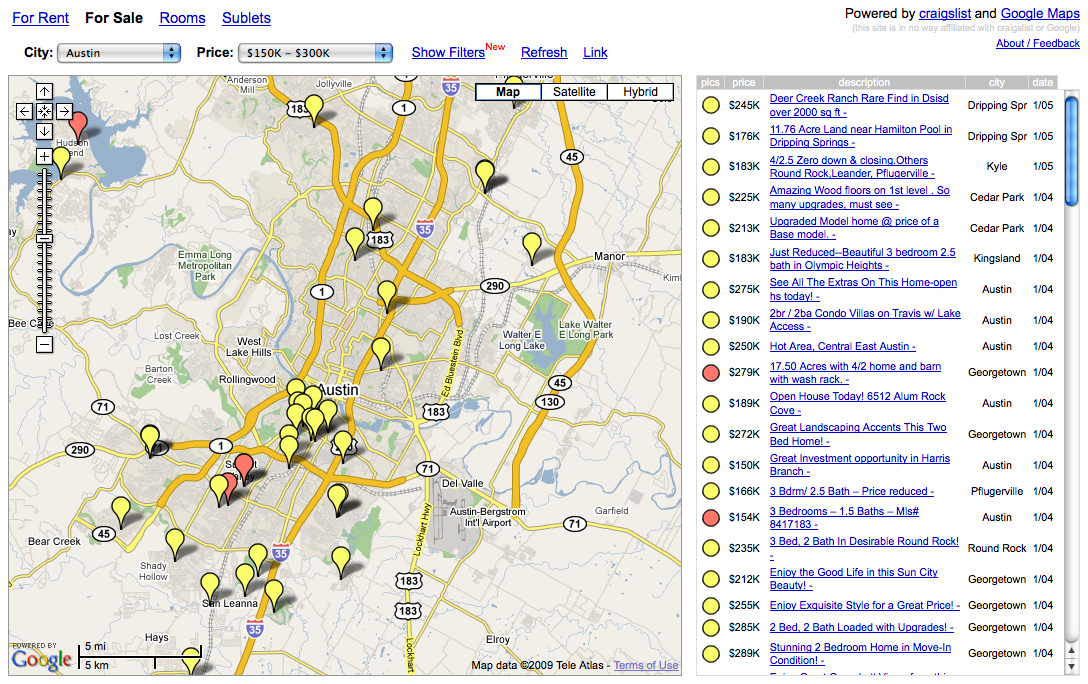

There is a marked difference between the earliest and current versions of these. But when you zoom out, each step incrementally advances existing behaviors. Over time, these incremental improvements make the underlying behaviors radically easier. Let’s consider a few examples: — Case Study: Google MapsNavigation is a long-standing human behavior. For many decades, we relied on paper maps until online maps like Mapquest and Yahoo maps emerged in the late 90s. Then in 2004, Google Maps arrived with draggable maps and real time zoom and was so much faster, smoother, and more intuitive. Maps combined technical innovations with thoughtful design details and felt like a massive leap forward. — People were enamored with Google Maps. Paul Rademacher, a software engineer, saw a way to use Maps to solve a personal problem. Paul had been looking for apartments and was frustrated there wasn’t an easy way to view up-to-date listings on a map. So he mashed together Google Maps and Craigslist and launched HousingMaps. Inspired by Paul’s mashup, Google Maps launched its API — allowing anyone to overlay geo-coded data on Google Maps. The first APIs were wildfire tracking, celebrity sightings, and bus routes. But the Maps API also enabled a quick start for many products like AirBnB, Uber, Yelp, Zillow, etc. — many of which still rely on the Google Maps API today. The API also helped improve Maps. In 2006, a product manager at Google, Avichal Garg, was visiting NYC and kept getting lost on the subway. He thought this was ridiculous in the day and age of Google Maps, so he sketched out a plan for building transit directions on the Maps API. He collaborated with an engineer working on routing algorithms, partnered with Portland’s transit agency, and built Google Transit. Google Transit rapidly grew in coverage and usage and eventually became a core feature of Google Maps. — Case Study: GmailCommunication has always been central to human life. As people moved farther apart, they relied on letters, telegrams, and phone calls to stay connected. Email was the Internet’s first big draw, but early versions were clunky and hard to use. Web-based providers like Hotmail and Yahoo! made it more accessible with friendlier interfaces. Still, email was slow, spammy, and hard to manage. Google engineer Paul Buchheit wanted something better. So he built the email client he wished existed — one that was:

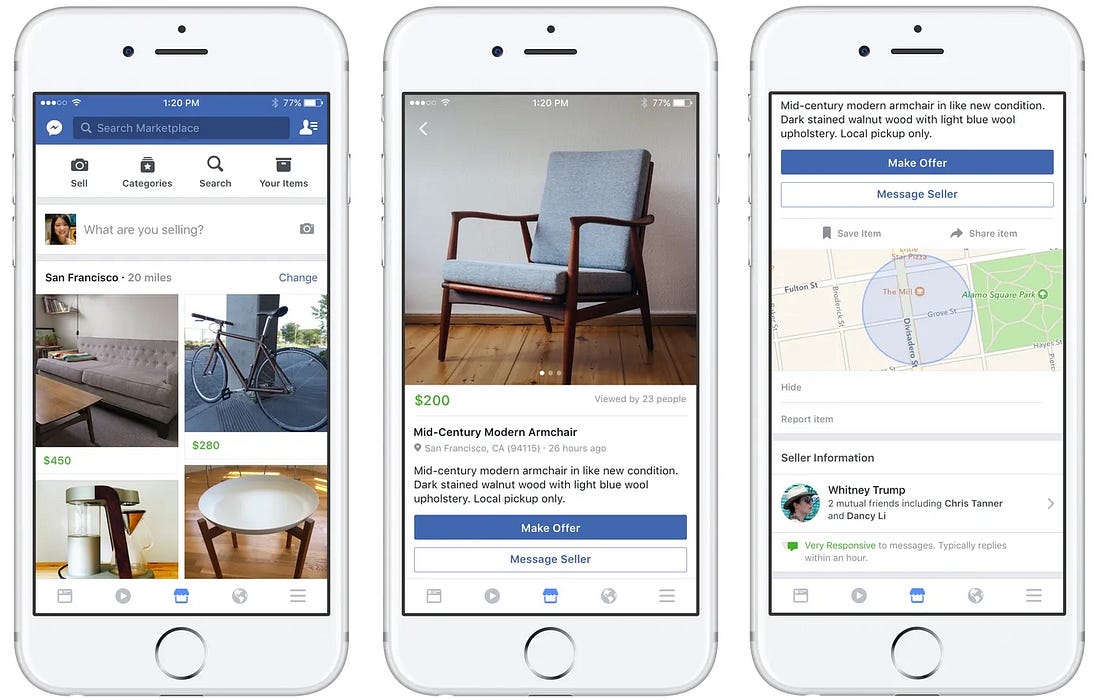

Paul was solving his own problem. Most users hadn’t yet hit these pain points — but he had. He was a lead user, and Gmail became the first email built to be truly digital: a communication hub and personal archive. — Case Study: Facebook MarketplaceBuying and selling is a deeply human behavior — from ancient markets to garage sales to Craigslist. But Facebook never set out to be a marketplace. Still, people used it as one. Deb Liu, a product manager at Facebook, was in a few Facebook Groups for new moms. She noticed many parents were buying and selling baby items (baby gear is expensive and only used for a short time). Groups hadn’t been designed for commerce, but the behavior was real — and growing. Deb studied these users, learned what mattered, and pulled together a team to build Marketplace. Facebook Marketplace made buying and selling items easier, safer, and more intuitive. Features like ratings, structured posts, location tagging, and direct messaging supported what users were already doing, but improved the experience. Facebook didn’t invent social commerce. But it noticed this user behavior, built for it, and amplified it. Note: For a the full history of building Facebook Marketplace, check out Deb Liu’s guest post for Lenny’s Newsletter. — So... Do Builders Innovate?Yes. But not always in the way we think. Designing and building isn’t about inventing. It’s about being aware of what people are already doing and creating improvements that make those behaviors easier, faster, and better. Designing and building amplifies user innovation. — What Can We Learn from Lead Users?Builders don’t have to be visionaries. But we do have to pay close attention. Here's what I’ve taken away from my many hours with Eric von Hippel, discussing lead user innovation:

— I have always believed it’s important to know and understand who you are building for. But I’ve started paying attention differently. Who is working at the bleeding edge — hacking things to work for them and their needs? The next big things are already happening. We just have to be aware. We have to see what lead users are doing, understand why, and figure out the best ways to make them better and accessible to everyone. |

Similar newsletters

There are other similar shared emails that you might be interested in: